Jack Kerouac’s The Subterraneans is a novel which can only truly be examined and understood while being read in a current setting by investigating how the time in which it was written affected the work. A new historical analysis of the novel’s portrayal of the 1950s San Francisco underground reveals the era’s attitudes toward race and the resultant cultural upheaval in America through a haze of run-on sentences and, as noted in the 1956 review of the novel in the New York Times, “the complete, almost schizophrenic disintegration of syntax" (Dempsey). This style is reflective or both the dizzying speed of change in the world of that time and the improvised nature of the jazz culture in which the novel is set.

The 1950s in the United States were turbulent times. The aftermath of World War II had left the country struggling with huge questions; the struggle for civil rights, the communist panic, and the disruption of traditional gender roles in the post-war environment (Rose the Riveter Can Do It!) had put many Americans back on their heels, not knowing how to deal with the new reality and all the many changes that came with it. People questioned mainstream culture, societal norms, and battled conformity and convention. From this maelstrom rose the beat poets, "a group of writers interested in changing consciousness and defying conventional writing" (A Brief Guide), and San Francisco became the heart of their movement.

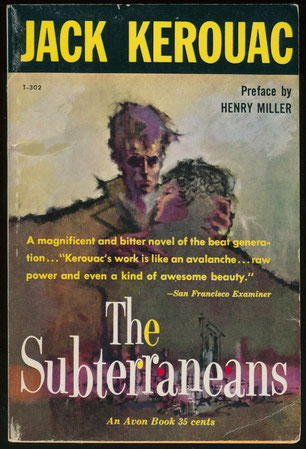

Jack Kerouac, considered a pioneer of the beat generation (as it came to be known), had written On the Road and it was received with great acclaim. The novel is still considered one of the great modern American works, and is a tenant of the beat movement. He wrote The Subterraneans soon after, and shortly following a love affair, which he fictionalized in the novel. Kerouac had been involved with a mixed-race woman, and his experiences and biases reflected in the novel are indicative of his, and America's, attitudes and stereotypes. Many would say we haven't progressed very far from this ignorance, even today.

"Kerouac used jazz, the new, free-form medium through which youth was expressing itself, as his entree into this world, and the writing style and young, carefree characters were his own literary jazz riffs. Like jazz, this is a sometimes sloppy and uncomfortable experiment."

In that time of great racial turmoil, Kerouac broke possibly the greatest cultural taboo in The Subterraneans by telling this story of this love affair between Leo Percepied, a white man, and Mardou Fox, a woman of mixed Native American and African-American heritage. He not only attempts to collapse the walls between the races but fully embraces the predominately Black jazz scene in which he sets his tale. San Francisco in the 1950s was the epicenter of this musical movement, and "such jazz greats as Ella Fitzgerald, Count Bassie, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, and John Coltrane...claimed their celebrity in part through their performances in the historic jazz clubs of San Francisco in the 1950s" (About Jazz). Leo's and Mardou's affair is symbolic of this new reality, a window into the changing cultural norms, and the monumental shifts in the arts and music. In race, and art, "Leo's love affair with Mardou...gives him what must have been access to a way of life most Americans in the '50s had never seen." (Wilson 312).

Kerouac's approach, while well intentioned, has been criticized by some, but seems to be a product of its time. Critic Joe Panish claims "Kerouac's romanticized depictions of and references to African Americans (as well as other racial minorities - American Indians and Mexican-Americas) betray his essential lack of understanding of African American culture and...social experience." He further argues that "American society, Kerouac says, desperately needs and infusion of the qualities embodied by her oppressed minorities: the existential joy, wisdom, and nobility that comes from suffering and victimization. Kenneth Rexroth, in his 1958 review of the novel, takes it a step further:

As a natural concomitant, Kerouac's attitude toward Negroes in what, in jazz circles, we can Crow-Jimism, racism in reverse. This book is just one stop removed from the "take me, you gorgeous black buck" trash of the lower paperbacks...I sincerely hop that the Negro girl of this sad, lost, marijuana-clouded, "therapist"-bedelived story never actually existed, because seldom has a man understood a woman less.

These criticisms document the thought that Kerouac's relative naivete to the ways of the cultures he portrays weakens the novel: another manifestation of the time of its creation. American wasn't yet used to this changing landscape, and even those trying to embrace it were doing do from a position of ignorance.

Even in the shadow of these truths, Kerouac used jazz, the new, free-form medium through which youth was expressing itself, as his entree into this world, and the writing style and young, carefree characters were his own literary jazz riffs. Like jazz, this is a sometimes sloppy and uncomfortable experiment. The culture of San Francisco became his way of making statements about what he thought it meant to be an American - an American of any race.

Mardou becomes the personification of the entire culture for Kerouac. She is the epitome of the unknown, the new, the other - white man Leo's guide into this unfamiliar world. Her aura, her nature, are intoxicating to Leo. In fact, right at the start of the novel, Leo remarks "Mardou Fox, whose face when first I saw it...made me think 'By God, I've got to get involved with that little woman' and maybe too because she was a Negro." He consistently refers to her as "the dark one," and talks about her "little brown body" and "her brown breasts," and it obvious there is a novelty, and excite in having a relationship with an "other" that Leo can barely contain. Reading this today, it is certainly uncomfortable, and reeks of cultural appropriation certainly, but Leo thinks of himself as the postmodern man, moving the beyond the usual limits of what was acceptable in polite and privileged society, but was that true? Or, is there an underlying wish to simply be rebellious, and to revel in it. As Mikelli states:

"Union with the racial other takes one further into the fringes of society and demarcates one's clear differentiation from the norm. There mere them of interracial romance poses a challeng to 1950s mainstream American's morality. By (partially, or a least erotically) reaching out towards Mardou's outsider status, Percepied attempts a considerable rupture not only with the racially biased attitudes of his time, but more expansively with the wider ideological and cultureal conventions of the 1950s."

Their romance becomes a statement, one of not just White and Black but one of shirking the chains society places on its people. Theirs becomes an archetypal story.

Even with the barriers broken, Leo's actions still occasionally echo the gender and race roles that were prevalent at the time, with a male-centric outlook that seems inconsistent with his "subterranean" attitudes: "[Mardou] would not have me hold her arm for fear people of the street would think her a hustler" and he replies, as he is measuring her value against his own accomplishments (and failing to acknowledge Mardou's independence), "In fact baby I'll be a famous and you'll be the dignified wife of a famous man so don't worry." Leo doesn't understand her fear and hesitation in having a white man's arm around her shoulders, and he devolves into a caricature of the 1950s man, out to take care of his little lady because she can't fend for herself. Later, Mardou again spurns Leo's attempts at a public display of affection, as Leo again speaks of "her usual insistence that I not hold her in the street or people'll think she's a hustler." Leo seems unable to wrap his head around her concerns, as he sees her through the prism of mid-century masculinity, the antiquated gender roles rearing their ugly head.

None of these themes seem to have been discussed in the mainstream reviews of The Subterraneans at the time of its publishing, which is interesting in that it seems society hadn't yet caught up with what Kerouac was trying to say, as exemplified by Dempsey's review in the New York Times, writing "[Kerouac] fails, it seems to me, in that he celebrates the self as something irresponsible, without ever identifying it with a world of objective, relevant values," while Rexroth wrote "It is sentimental, naive, pretentious and full of shocking lack of understanding of the world it describes. Since this is presumably the world of the author's own life, this is a pretty serious indictment."

It is now obvious that this story of an interracial romance broke down barriers and is a landmark book, even while the author struggled to understand his subject matter and, most probably inadvertently, may have reinforced negative stereotypes about these same subjects. It is a flawed, but courageous, book, and offers fascinating insights into how we were, and how we are. If we look back in 50 years on the books authors are writing today, I wonder if they will be such a treasure trove, a veritable time capsule, of the bleeding edge of anti-establishment thinking. I very much doubt it.

References

“A Brief Guide to the Beat Poets.” Poets.org. Web. 22 October 2018.

Dempsey, David. "The Subterraneans." New York Times 23 February 1956.

Mikelli, Eftychia. "A Postcolonial Beat: Projections of Race and Gender in Jack Kerouac's 'The Subterraneans." ATLANTIS. Journal of the Spanish Association of Anglo-American Studies. December 2010 27-42.

Panish, Joe. "Kerouac's 'The Sunterraneans: A Study of 'Romantic Primitavism." MELUS. Autumn 1993 107-123.

Rexroth, Kenneth. "Jack Kerouac - 'The Subterraneans." San Francisco Chronicle. 16 February 1958.

Write a comment