“Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.” It is a coda, and a warning. Look too closely, and you may not like what you see. Rarely has one line of dialogue so perfectly captured the plot, the emotion, and theme of a film.

Jack Nicholson’s character Jake Gittes is a successful private investigator, a man who left behind law enforcement to make a good living following around wandering husbands and taking pictures of their affairs for their bereaved wives. He accepts a case concerning one Hollis Mullray (Darrell Zwerling), chief engineer of Los Angeles Water and Power, who is suspected of cheating by his wife, Evelyn. This is just the outer layer of the onion, however, and as each layer is pealed the mystery grows deeper and more malevolent. It is a testament to the skill of the filmmakers that a film about drought and the theft of water could be such a labyrinthine, nihilistic road to tragedy.

Chinatown may have been made in 1974, but this is classic film noir. Jerry Goldsmith’s jazzy, mournful brass score weaves through every scene, music that would be perfectly at home in an art deco nightclub. Sunlight slices through half-closed blinds, leaving half of everything, and everyone, in shadow, a visual representation of moral ambiguity. Rat-a-tat, hard boiled dialogue flies like bullets: “I goddamn near lost my nose, and I like it. I like breathing through it. And I still think that you’re hiding something.” Corrugated glass doors close on every office, so you can only see hints of what is going on inside. There are very few heroes in this world, and far too many villains.

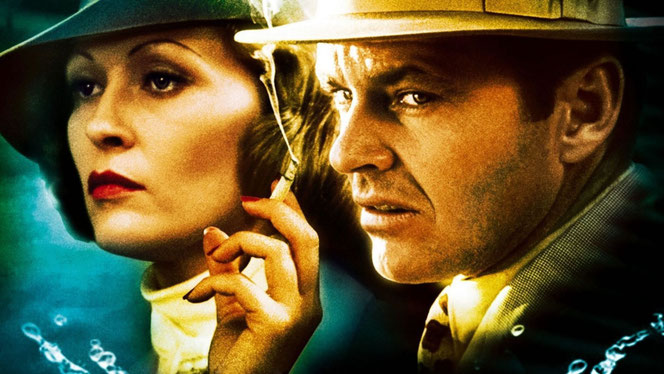

Nicholson’s Gittes, Faye Dunaway’s Evelyn Mullray, and John Huston’s Noah Cross are the three-headed monster of the film, but Nicholson is in every scene, and the corruption and rot are observed through his eyes. Make no mistake, rot is the central theme of the movie – moral, societal, governmental, familial. No institution makes it through Chinatown unsullied. Robert Towne’s screenplay and Roman Polanski’s direction are shiny on the surface – L.A. sparkles in the sunlight, the men are dressed to the nines in sharp suits with fedoras and the women wear striking, stylish dresses. Cigarette smoke obscures many of the scenes, a fog hanging over everyone. The scenes shot outside, in the blazing sun, are steeped in browns, beiges, and whites, reflecting a city suffering with drought, save for the orange groves, which are green, lush, and full of fruit even as the roads through them are dusty and barren. While Chinatown does not necessarily follow the well-worn noir aesthetics of deep shadows and dark, wet streets, the way it handles the metaphoric darkness is a comment on that bright new California life that hides the real decay.

"'Chinatown' is a tone poem, a nihilistic exclamation that no matter what you do, the rot will get you, too."

Jack Nicholson plays Jake in an understated, naturalistic performance, without much of the Nicholson mania or showboating we’ve become used to seeing in films like Batman, The Shining, and A Few Good Men. Gittes is happy making a decent living and keeping his head down, but his inherent thirst for the truth (a remnant of his life in law enforcement, to be sure) shoves him into this dark underworld, and he will not be leaving the same man he was before the journey.

Faye Dunaway gives a strong performance as Evelyn, a woman with a steely demeanor that cracks at virtually any mention of her father. When her character is introduced, she speaks directly, with that mid-Atlantic accent we are all used to hearing from upper-crust characters in films of the middle of the last century. Jake takes her case, even after completing his original job of tailing her husband. She connects with him, and as she gets more comfortable with Jake, this façade falters, and her real personality breaks through. During an early exchange with Jake, Evelyn even has trouble even saying “my father” without hesitating and her voice cracking. Later, after Evelyn and Gittes spend the night together, they discuss her father’s ownership of the club. They are both nude, and she is seen topless, without a care that her lover is seeing her body. When Jake says he saw her father, however, she instinctually covers her breasts – an early signal that their familial relationship is traumatic and more damaged than one could ever know. All is not what it seems with Evelyn, a classic femme fatale.

John Huston, the director of noir classics The Maltese Falcon and Key Largo, plays her father, Noah Cross, like a friendly dragon that will burn you to death while delivering a big, homey smile. He speaks with a slight Southern accent, and his big, expressive mouth is curled in a sinister grin. He is a man used to getting what he wants, and destroying anyone in his way. Upon their first meeting, Cross uses subtle tactics to put Jake in his place, pronouncing Gittes’s name as “Gits,” even though Jake corrects him multiple times, as if getting this insignificant gnat’s name right is not even worth Cross’s time. He is a man with much bigger goals than Gittes could comprehend. “Why are you doing it? How much better can you eat? What could you buy that you can't already afford?” Jake asks him. “The future, Mr. Gittes!” is the response. He wants to control the water, the government, and his offspring. Only then can he cement his legacy. He must possess all. “How many years have I got? She's mine, too,” he says about his youngest daughter.

Every line of dialogue in Chinatown advances the plot, and every scene uncovers more of the mystery or gives insight into the personalities of the characters. Every interaction Jake has with city officials is unhelpful or a barrier, from City Hall’s corridors of power to a clerk at the Hall of Records. Chinatown is saying not to trust what our eyes are showing us, that what we see is not what is real, and the symbolism from broken glasses, to birthmarks in eyes, to fatal gunshots through those same eyes echoes through the film. American Beauty, another deconstruction of American families (albeit this one of suburbia), said “Look Closer.” In Chinatown, looking closer will get you killed.

Ultimately, Chinatown is a tone poem, a nihilistic exclamation that no matter what you do, the rot will get you, too. All of the characters’ machinations and heroic deeds ultimately do nothing but advance, and complete, the villains’ goals. This film drips with menace and tragedy and pessimism, and all the light in the sun-drenched, dry desert town of Los Angeles is not enough to illuminate the dark corners where men like Noah Cross thrive. Jake took Evelyn’s case, even after the original job was completed. His dedication, in the end, may have cost him everything. Chinatown makes the case that maybe, just maybe, he should have stayed out of it, should have looked out for number one.

“Are you alone?” Jake is asked at one point. His response? “Aren’t we all?”

Write a comment